The Gilead Anti-Infectives Forum is a promotional website intended for healthcare professionals in the UK and Ireland, and has been designed, built, and funded by Gilead Sciences Ltd.

The fungal kingdom includes as many as 6 million species, 600 of which are associated with humans, either as commensal species or as pathogens that can lead to invasive fungal infections (IFIs).1 IFIs are a leading cause of mortality in intensive care units (ICUs),2 haematology3,4 and HIV settings.5-7 With resistance to antifungal treatment on the rise,8,9 you can fight back against the threat by understanding the different fungal pathogens, what invasive fungal diseases they cause, and how they can be treated.

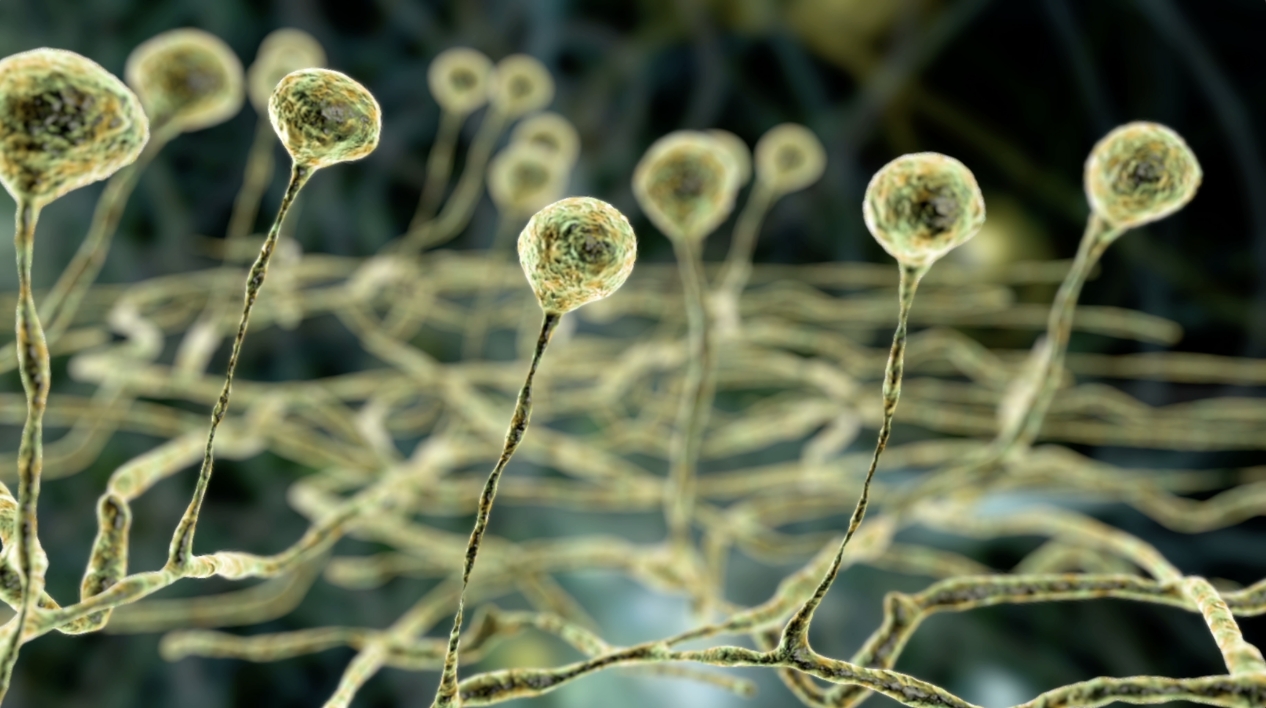

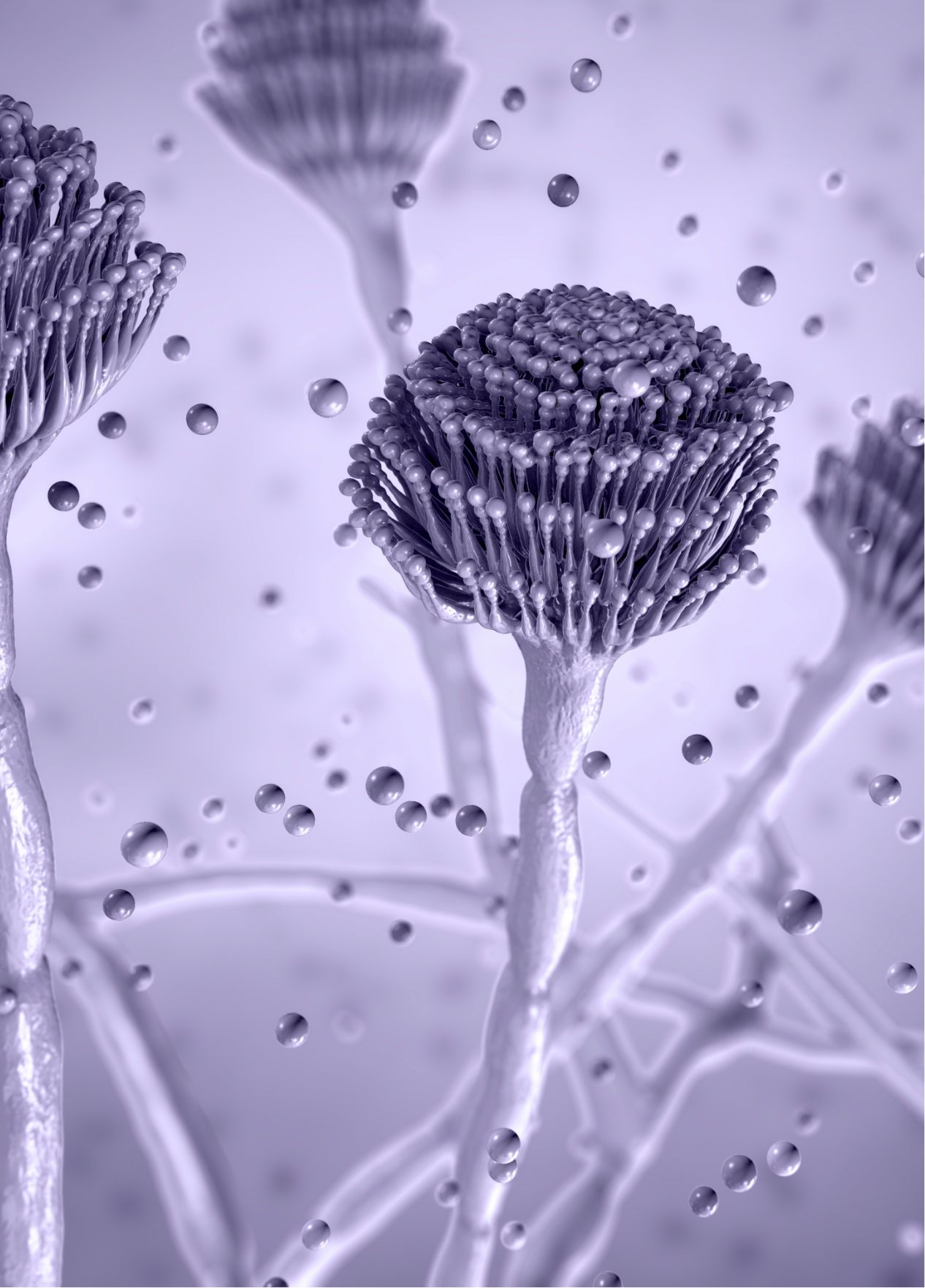

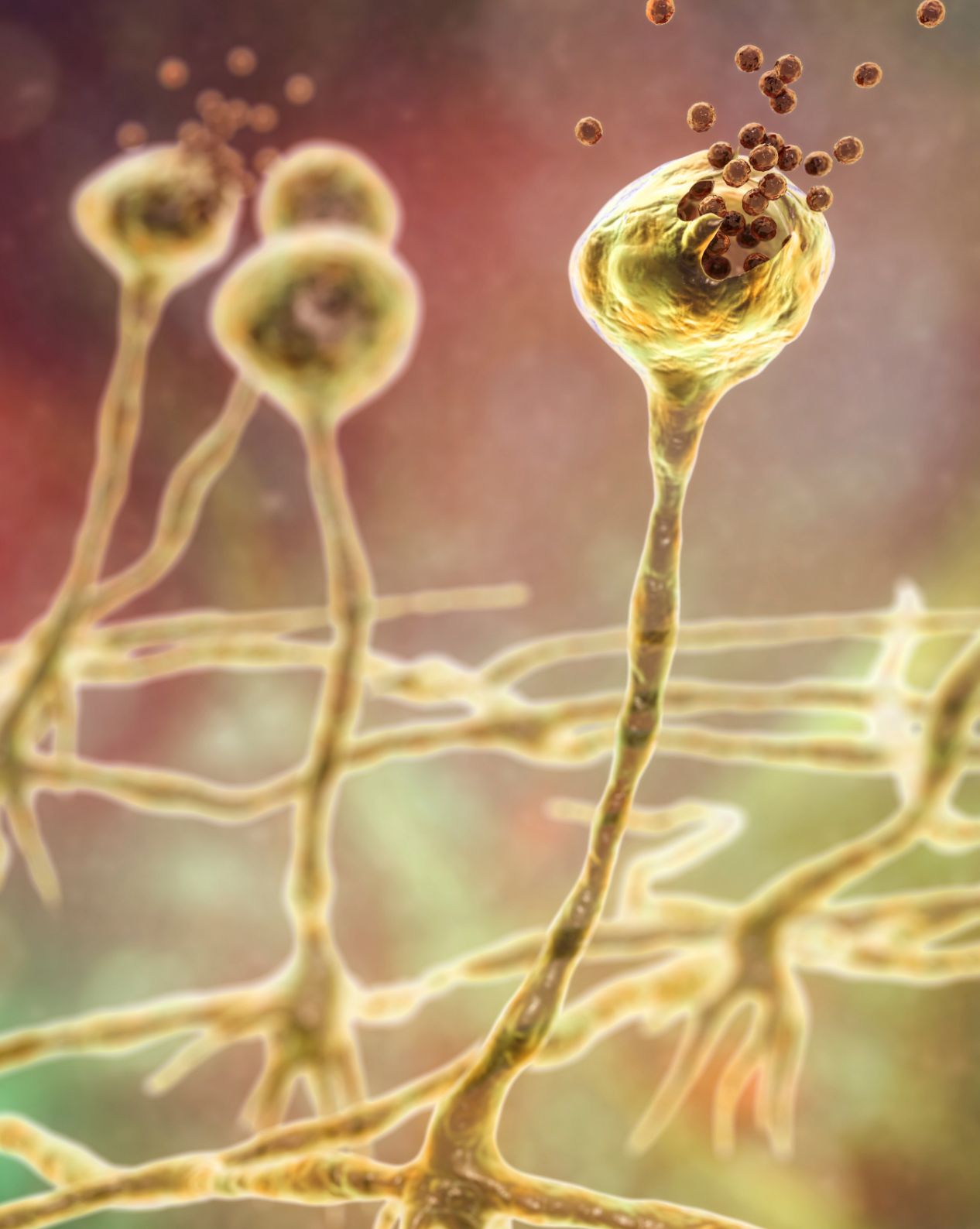

Aspergillus is a type of ubiquitous saprophytic fungus that can cause invasive infection (aspergillosis) in those who are immunocompromised or have respiratory disease10,11

Aspergillus is a type of ubiquitous saprophytic fungus that can cause invasive infection (aspergillosis) in those who are immunocompromised or have respiratory disease10,11

Most cases of invasive aspergillosis are caused by A. fumigatus, but non-fumigatus Aspergillus species are becoming more common12

Most cases of invasive aspergillosis are caused by A. fumigatus, but non-fumigatus Aspergillus species are becoming more common12

The microscopic spores (conidia) present in Aspergillus species are found in the air, soil, dust, decaying vegetation and many other settings; it has been estimated that in excess of 100 A. fumigatus conidia are inhaled by an average adult every day11,13

The microscopic spores (conidia) present in Aspergillus species are found in the air, soil, dust, decaying vegetation and many other settings; it has been estimated that in excess of 100 A. fumigatus conidia are inhaled by an average adult every day11,13

In most individuals, inhaled conidia will be cleared by the alveolar macrophages, without affecting health. However, Immunocompromised patients are extremely susceptible to local invasion of respiratory tissue by deposited conidia, resulting in invasive growth of hyphae13

In most individuals, inhaled conidia will be cleared by the alveolar macrophages, without affecting health. However, Immunocompromised patients are extremely susceptible to local invasion of respiratory tissue by deposited conidia, resulting in invasive growth of hyphae13

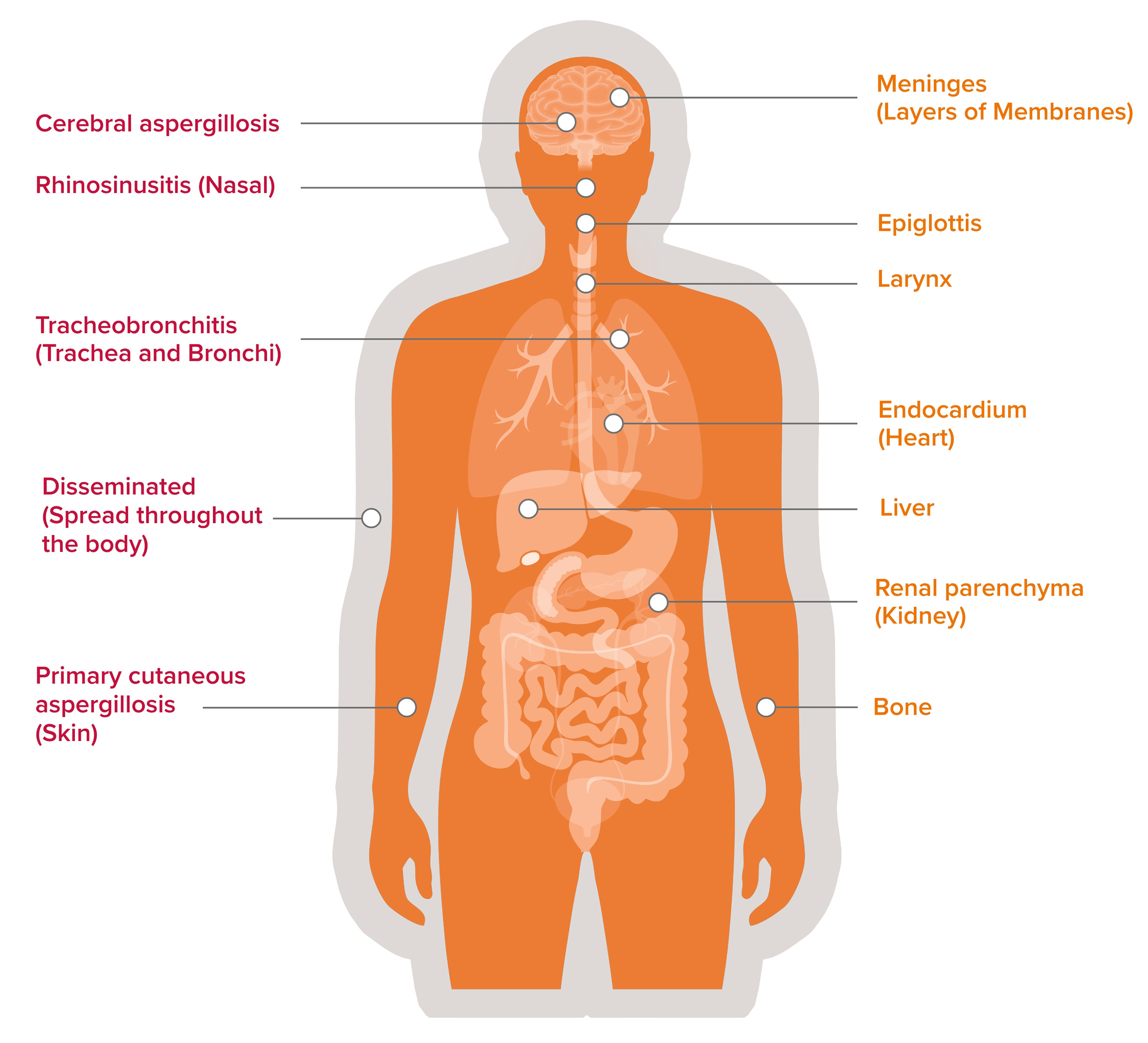

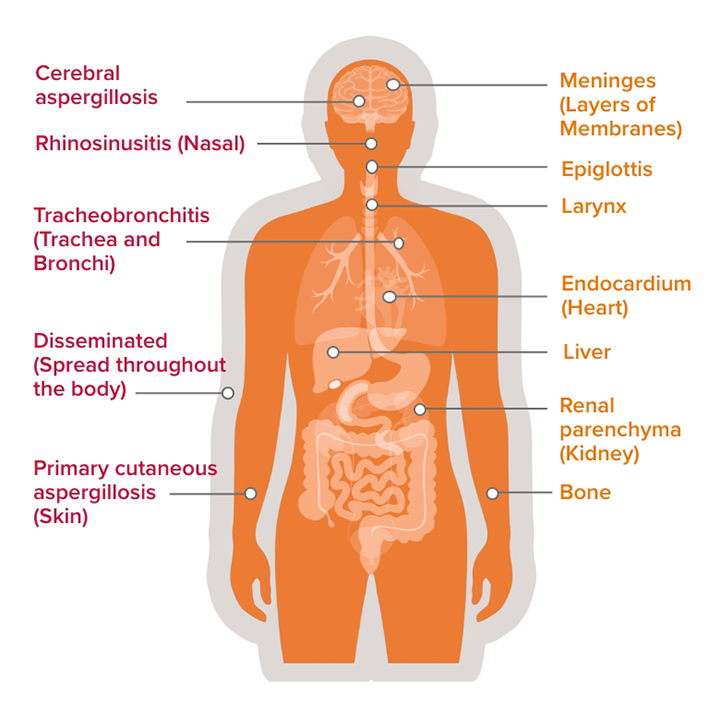

Common sites of infection

Uncommon sites of infection

NB this list is non-exhaustive

Aspergillus spp. infections in immunocompromised hosts range from pulmonary aspergillosis (the most common site of infection), tracheobronchitis, primary cutaneous aspergillosis (especially in neonates and children), rhinosinusitis, cerebral aspergillosis, to disseminated aspergillosis.13,14 Other unusual sites have also been recorded, including epiglottis and larynx, meninges, endocardium, and renal parenchyma, as well as bone and liver.14

Invasive aspergillosis (IA)

AmBisome® (liposomal amphotericin B) demonstrates in vitroa fungicidal activity against major Aspergillus species, including A. fumigatus and A. flavus.22

a. Caution must be taken when extrapolating in vitro data in the clinical setting.

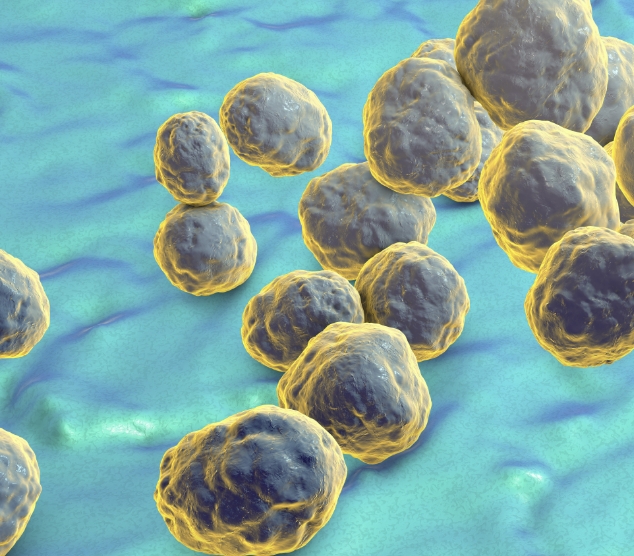

Candida is a type of yeast that can become invasive and cause serious infections in internal organs (invasive candidiasis) and the bloodstream (candidaemia) in patients at risk, such as those in ICUs or those with a weakened immune system23

Candida is a type of yeast that can become invasive and cause serious infections in internal organs (invasive candidiasis) and the bloodstream (candidaemia) in patients at risk, such as those in ICUs or those with a weakened immune system23

A common route of infection is through central venous catheters that are needed by patients in the ICUs for extended periods of time23

A common route of infection is through central venous catheters that are needed by patients in the ICUs for extended periods of time23

Candida species account for 70-90% of IFIs24

Candida species account for 70-90% of IFIs24

Candidaemia is one of the most common IFIs in immunocompromised ICU patients25

Candidaemia is one of the most common IFIs in immunocompromised ICU patients25

The most common Candida species that cause infections globally are C. albicans, Nakaseomyces glabratab, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei,23,26-28; however, C. auris is an emerging, multi-drug resistant, fungal pathogen causing concern globally23,28,29

b. Formerly known as Candida glabrata

The most common Candida species that cause infections globally are C. albicans, Nakaseomyces glabratab, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei,23,26-28; however, C. auris is an emerging, multi-drug resistant, fungal pathogen causing concern globally23,28,29

b. Formerly known as Candida glabrata

AmBisome® demonstrates in vitroa fungicidal activityc against a multitude of Candida species, including C. albicans, N. glabratab, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, and C. tropicalis32

a. Caution must be taken when extrapolating in vitro data in the clinical setting. b. Formerly known as Candida glabrata. c. The majority of clinically important fungal species seem to be susceptible to amphotericin B, although intrinsic resistance has rarely been reported, for example, for some strains of S. schenckii, N. glabratab, C.krusei, C. tropicalis, C. lusitaniae, C. parapsilosis and A. terreus.

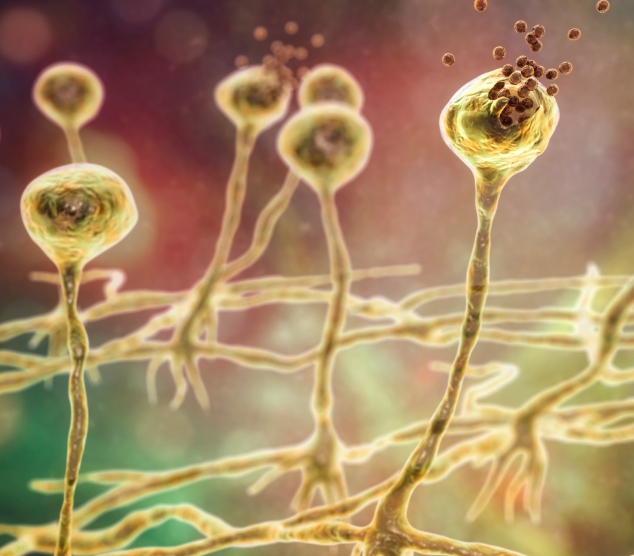

Mucormycetes is a genus of mould fungi that can cause a serious, but rare, fungal infection (mucormycosis) in at-risk patients23

Mucormycetes is a genus of mould fungi that can cause a serious, but rare, fungal infection (mucormycosis) in at-risk patients23

These environmental fungi live in soil and decaying organic matter,23 and can cause rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cutaneous or disseminated infection in predisposed individuals33

These environmental fungi live in soil and decaying organic matter,23 and can cause rhinocerebral, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cutaneous or disseminated infection in predisposed individuals33

The most common species are Rhizopus species and Mucor species34

The most common species are Rhizopus species and Mucor species34

AmBisome® is recommended by the ECMM/MSGERC as a treatment of choice for mucormycosis42

Cryptococcosis is an invasive fungal infection affecting immunocompromised patients, usually caused by Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii43

Cryptococcosis is an invasive fungal infection affecting immunocompromised patients, usually caused by Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii43

These two species are commonly found in soil, decaying wood, tree hollows and bird droppings, and can cause infection through inhalation23,43

These two species are commonly found in soil, decaying wood, tree hollows and bird droppings, and can cause infection through inhalation23,43

Cryptococcal meningitis, predominantly caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, affects people living with advanced HIV, and has an estimated 223,100 cases globally each year44

Cryptococcal meningitis, predominantly caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, affects people living with advanced HIV, and has an estimated 223,100 cases globally each year44

Symptoms of cryptococcosis depend on the location of the infection (lungs, brain, skin or other organs), but can include coughing, breathlessness, and fever when in the lungs23,45-51, and headache, fever, nausea and vomiting, light sensitivity and confusion when affecting the brain23

Symptoms of cryptococcosis depend on the location of the infection (lungs, brain, skin or other organs), but can include coughing, breathlessness, and fever when in the lungs23,45-51, and headache, fever, nausea and vomiting, light sensitivity and confusion when affecting the brain23

AmBisome® demonstrates similar efficacy to amphotericin B deoxycholate with fewer adverse events, in people living with advanced HIV with acute cryptococcal meningitis.55

UK-AMB-0695 | November 2023